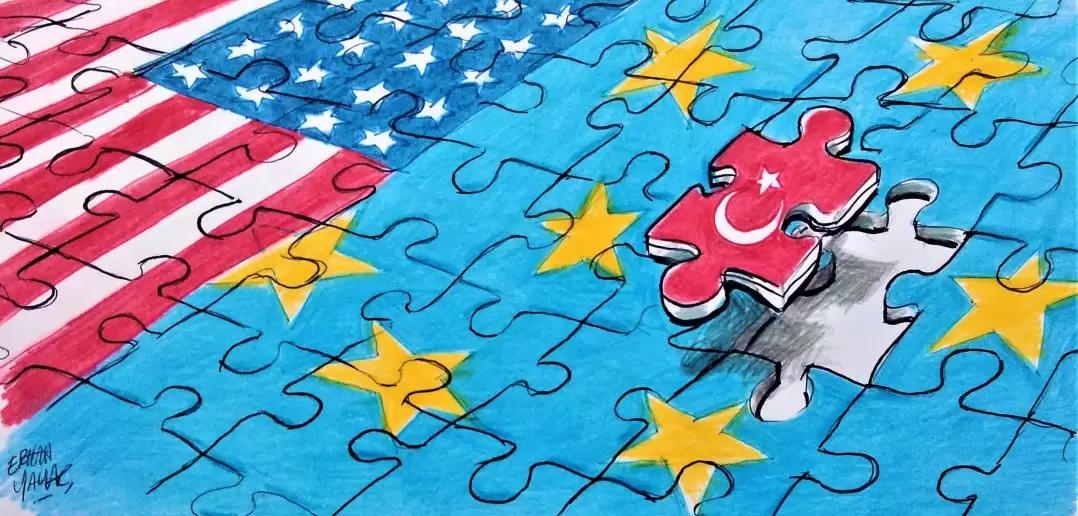

The Turkey-West Conondrum

by Ali Tuygan

Almost five years ago I said that the alliance between Türkiye and the US which, despite ups and downs had stood the test of time, was under considerable strain, and the so-called “telephone diplomacy” which did not allow for an in-depth exchange of views raised more questions than it resolved. This was the time when President Trump, despite having sent the most discourteous letter in the history of modern diplomacy to his Turkish counterpart, was still Ankara’s only “friend” in Washington.

Since then, the decline has continued. I went over what I read and wrote about the relationship during the last five years, especially after President Biden’s coming to the White House, and I could hardly see a word of optimism.

Five years ago, the bilateral foreign policy agenda was essentially about S-400s, the US support for the PKK-YPG, and cases before the US courts. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Turkish-Greek confrontation is now added to the list of problems. Because Washington, having seen that Ankara remains determined to uphold the 1936 Montreux Convention regulating passage through the Turkish Straits, decided to open a land corridor to the Black Sea to bypass the restrictions imposed by the Convention. And Greece was the only other NATO ally that could help realize the project. Thus, the port of Alexandroupolis became the gate of this land corridor. Some may also see this as the final nail in the coffin of “Canal Istanbul”, the “crazy project” even as its proponents called it at the time of its launching.

The Mitsotakis government already enjoying the advantages of its EU membership and emboldened by the signing on October 14, 2021, the “US-Greece Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement” (MDCA) chose to take a tougher line against Türkiye. Was Ankara, where foreign policy has for long become a mere tool of the government’s domestic policy upset? “Yes” and “no”. Yes, because it added a further dimension to Turkish-American tensions, no because Ankara also likes tough talk especially when the economy is in steep decline making distractions welcome especially when the country is only months away from a supposedly critical presidential election.

Despite the many unknowns like in any other authoritarian country, one can say with certainty that today, the relations between Türkiye and the West are at their lowest point since the founding of the Republic.

Most Western governments now regard JDP’s Ankara as only a “nominal ally” if not an adversary, and despite the search for alternative arrangements, they cannot completely turn their back on a country that enjoys a geo-strategic location surrounded by three seas and joining Asia and Europe during times when the Russia-US and Russia-Europe relations are in steep decline. Turkey is also a unique window into the Middle East. Sadly, it has also acquired a critical role in Europe’s dealing with its refugee problem. Moreover, Turkey has a history of democracy despite its ups and downs. It has important investment and trade relations with Europe. And it seems that a majority of Turks wish to restore democratic rule and the country’s Republican traditions.

But does this also include a desire to restore relations with the West? Hard to tell.

Because the Turkish government’s decade-long anti-Western rhetoric has found a receptive ear among the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) faithful. And the anti-Western sentiment is also on the rise among those yearning for Turkey’s return to the democratic path. Many believe that the West has no interest in Turkish democracy so long as the country remains “anchored” in the West and “behaves”. Some, to prove their point, draw attention to the fact that the West has enjoyed cozy relations with Middle East countries with no history of democracy, and no respect for rule of law.

In recent years, books and papers have multiplied not only about the Western plans to carve up the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War but even today’s Türkiye. Readers tend to focus on these plans, paying less attention to how the decadent Empire and its decadent sultans managed to turn the country into a land to be easily gobbled up had Ataturk not raised the flag of the War of Independence against the victors of the War and their lackeys in Türkiye.[i] While the disappointment with the West is understandable and largely justified, it tends to overlook the fact that none of those authoritarian Middle East countries are members of either the Council of Europe or NATO and that a total rupture with the West would mean a final goodbye to democracy.

Historically, the Turkish-Greek relationship has been an important chapter of Türkiye’s relations with Europe. But, beyond a shadow of a doubt, this relationship also has its independent character. Leaders of Greece and Türkiye would be wise not to allow the relations between their countries to become a footnote of the Russia-US confrontation when some reports suggest that all is not quiet on the Western Front.[ii] Moreover, Türkiye and France, and Greece and Germany are not neighbors. But Greece and Türkiye are.

As for Türkiye’s relations with the West, in the broad Middle East, there can always be surprises like President Biden’s visit to Saudi Arabia. But in roller-coaster relationships, surprises seldom mean fundamental change. It was widely reported last week that Saudi Arabia and Russia, acting as leaders of the OPEC Plus energy cartel, agreed last Wednesday to their first large production cut in more than two years in a bid to raise prices, countering efforts by the United States and Europe to choke off the enormous revenue that Moscow reaps from the sale of crude.

With its institutional dimensions, Türkiye’s relationship with the US and Europe is far more complicated. It has a heavy legacy of history. It is handicapped by disagreements on the so-called “common values” and bad chemistry. And times are changing, an emerging new world order, global shifts in power, and shifts of axis have become current topics. Thus, regardless of the outcome, soon after Türkiye’s next presidential election will come the day of reckoning for the Türkiye-West relationship. Because the agenda will not be a reset but defining the parameters of a new relationship. Thus, it will be a huge challenge for both sides.

————————————————————————————————————-

[i] https://diplomaticopinion.com/2018/11/11/armistice-day-and-ataturk/

[ii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/10/08/norway-gas-prices-supply-europe/